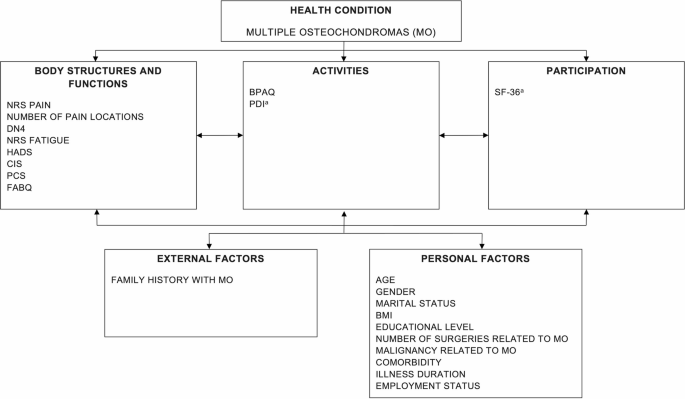

Physical activity level and health-related quality of life in adults with multiple osteochondromas: a Dutch cross-sectional study

To our knowledge, this is the first large-scale study on PAL and HRQOL of patients with MO that also provides insight into associated sociodemographic, illness-related and psychological factors. Our findings suggest that patients with MO experience significantly lower PAL and reduced physical HRQOL—compared to gender-matched healthy controls—while reporting similar mental HRQOL. An association between PAL and HRQOL could not be confirmed in our study population. However, several patient characteristics and psychological factors were associated with PAL and HRQOL in this study—many of which are clinically modifiable and may serve as targets for future interventions. Below, we discuss these findings in relation to our five pre-specified hypotheses.

Hypothesis (1): patients with MO have a lower HRQOL and PAL than healthy controls.

Patients with MO have a significantly lower PAL and physical HRQOL than gender-matched healthy subjects, but similar mental HRQOL. A minimal clinical important difference (MCID) of 2.5–5 points for physical HRQOL of patients with rheumatoid arthritis has been reported44, meaning that the lower physical HRQOL (> 5 points) for both men and women with MO compared to healthy subjects can be interpreted as a clinically worse state. To the best of our knowledge, the MCID of the BPAQ has not yet been reported in patients with musculoskeletal complaints, underscoring the need for future research.

Hypothesis (2): a higher PAL, after controlling for other factors, is significantly associated with a higher HRQOL in patients with MO.

A positive relationship between the PAL and HRQOL in MO could not be confirmed. While this contrasts with some prior findings in chronic musculoskeletal populations25, it is plausible that other clinical or psychological factors mediate or moderate this relationship in MO. One likely explanation is the heterogeneity of disease severity and functional limitations; in those with severe skeletal deformities and restricted joint motion, increased physical activity may not translate into functional gains or improved HRQOL. Further studies are needed to better understand the impact of disease severity in MO on the association between PAL and HRQOL.

Hypothesis (3): a higher BMI, higher pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with the PAL.

The negative relationship between PAL and higher BMI, pain intensity, and depressive symptoms in MO-patients has been confirmed and is in accordance with other populations45,46. A longitudinal study on the reciprocal relationship between physical activity and depression showed that performing moderate to vigorous physical activity at least once a week is associated with lower depressed mood45. This should be targeted in the treatment plans of MO-patients. Patients’ PAL is positively associated with having a paid job and these patients had, besides a higher work-index, also a significantly higher PAL sport-, and leisure-index (p < 0.001) than patients who did not have a paid job. Being able to work seems an important contributor to patients’ PAL. More anxiety was also related to a higher PAL, while in contrast previous studies reported that lower levels of anxiety were related to higher levels of physical activity46,47. However, anxiety only contributes 1% of the total explained variance, which is rather negligible, and only 11.7% of the total patient sample has scores above the cut-off score (> 7) for anxiety37. Patients who experienced malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma into a chondrosarcoma in the past had a significantly lower PAL. These results are in line with findings on activity limitations after bone cancer48.

Hypothesis (4): female gender, higher BMI, comorbidity, higher pain and fatigue, physical disability and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with physical HRQOL.

Our study confirmed this hypothesis for all factors except female gender. Ambiguity exists on whether MO affects men and women differently3,8,9. We hypothesized that female gender would be negatively associated with PAL and physical and mental HRQOL, but gender was not retained in any of the regression models. This suggests that, when controlling for other potential factors, gender is not an important contributor. In our study, significantly more comorbidities, neuropathic pain, higher level of pain, pain-related disability, fatigue, anxiety and lower physical HRQOL were reported by females. Of note, deformities and functional limitations, such as restricted joint motion, were not assessed in this study and cannot be compared between genders. These differences in phenotypes could be a confounding factor worth investigating in future research.

Previous studies in chronic musculoskeletal disease have established an association between activity limitations and a lower HRQOL11,18. In our study, greater pain-related disability was linked to reduced physical HRQOL in patients with MO. Although we did not find a direct relationship between physical activity level (PAL) and HRQOL, previous literature suggests that PAL may indirectly influence HRQOL through its effects on pain, fatigue, and psychological distress49,50. These findings imply that interventions aimed at reducing pain-related disability could potentially improve physical HRQOL in this patient group. Further research is needed to confirm these pathways. Consistent with other chronic musculoskeletal pain populations, fatigue intensity, age, BMI, and pain characteristics, such as more pain locations and pain intensity were also negatively related to patients’ physical HRQOL10,50. In contrast to the study of D’Ambrosi et al. (2017), more surgical interventions (6–10 interventions) were negatively related to physical HRQOL. Conversely, the lower HRQOL observed may indicate a more severe phenotype that might require additional surgical interventions, potentially explaining this outcome.

Higher anxiety scores were positively related to physical HRQOL, although only explaining 1.8%, while the opposite direction was expected15. The SF-36 PCS score increases with 0.447 for every point higher on the anxiety subscale, but the reason for this inversed directionality is unclear. Surprisingly, depressed mood and pain catastrophizing did not remain in the model15,18, but fear-avoidance beliefs were negatively associated with physical HRQOL18. On average, it seems that psychological factors, which are often reported and negatively associated with physical HRQOL in other chronic pain populations13,18, are less present in (or recognized by) patients with MO. Our sample is merely a cross-section of the total population and included patients who do not necessarily have high care needs. It is plausible that differences exist in the presence of psychological factors and their impact on HRQOL between patients with different care needs. Borsbö et al.15 identified four subgroups based on depression, anxiety, catastrophizing, pain intensity and duration in chronic pain patients (spinal cord injury, whiplash and fibromyalgia). Two subgroups who scored high on psychological factors reported lower HRQOL and more disability than the two subgroups who scored (relatively) low on psychological variables15. Subgrouping of patients based on psychological variables could have added value when investigating HRQOL.

The educational level was also positively related to physical HRQOL, in accordance with previous results of patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain10,49,50. Salaffi et al.10 hypothesized that a higher education may lead to more self-efficacy and consequently to a better self-management of disease-related symptoms and disability.

Hypothesis (5): female gender, being single, a lower educational level, malignancy, more surgical interventions, higher intensity level of pain and fatigue, and presence of psychological factors are negatively associated with mental HRQOL.

In the final mode female gender, being single, malignancy and amount of surgery were not retained. Conversely, higher levels of anxiety and depressed mood were related to lower mental HRQOL, similar to healthy subjects15,51. While pain intensity did not remain in the final model, fatigue intensity was negatively associated with mental HRQOL. This result shows that in MO like other musculoskeletal disorders, fatigue has a stronger impact than pain on mental HRQOL16,52. The negative association of a higher educational level with mental HRQOL is unexpected, as it seems to be positively related to self-efficacy10,50 and adequate coping skills which mediate the relationship between sense of coherence and mental HRQOL53. An underrepresentation of patients with a primary educational level (n = 2) and, surprisingly, slightly higher mental HRQOL experienced by these patients than those with a higher educational level in our sample seems to underlie this result.

In our sample, more pain-related disability was slightly positively related to mental HRQOL, while other studies in chronic pain patients found more perceived disability to be related to lower overall HRQOL15,54. A possible explanation could be that patients with MO have adapted to their situation55, keeping in mind that nearly all patients are diagnosed at a young age, and by the age of 12 years7 at the latest. Patients’ adaptation to their chronic illness and disability, and its relationship with HRQOL should be explored further. On average, the PDI score is relatively low. This may be partly explained by our recruitment from both an expertise center as through the patient association. It is possible that our patient sample had a lower intensity of care compared to patients who are hospitalized or had recent surgery.

Limitations

First, reference scores from the general Dutch population used to compare patients’ PAL and HRQOL scores date from 198228 and 199829, respectively, and may be less representative of the current population.

Second, as this is a cross-sectional study, conclusions on causality cannot be drawn but require a longitudinal study.

Due to the recruitment procedure (expertise center and patient association) there is a possible under- or overrepresentation of persons who are asymptomatic or experience only mild symptoms. However, the number of completed questionnaires was high and patient characteristics showed a large degree of variability between patients, suggesting that both patients with no or mild and patients with severe symptoms were represented in our sample. Nevertheless, a potential selection bias cannot be excluded.

Even though the range of scores on psychosocial and symptom-related variables was large, we did not analyze our data based on known subgroups identified in other chronic disorders15. Due to the knowledge gap on aforementioned associations in patients with MO, a first exploration of the PAL and HRQOL, and associated patient-specific factors, symptom severity and psychological factors was necessary. A subsequent exploration of subgroups in the MO population could further clarify the association between psychological and symptom-related variables and the dependent variables (PAL and HRQOL). These additional insights could provide supplementary information for health professionals and support the development of individualized treatment programs.

Due to our study design, we relied on self-reported measures, which are susceptible to known biases such as recall bias. Subjective estimates of PAL may also differ from objectively measured data. For this study, we preferred a large sample size over the ‘objectivity’ of outcome measures. To minimize participant burden and maximize recruitment, we chose self-reported methods rather than multiple in-person assessments or additional objective measures.

Regarding our sample size, we did not perform a formal a priori power calculation (as noted in the Methods). Instead, we aimed for a convenience sample, as large as feasible within the study project’s constraints, to obtain the best possible estimates of our outcomes. We successfully enrolled a substantial cohort of individuals with MO—despite the rarity of this condition—which allowed us to develop robust regression models based on our theoretical framework. While additional associations may emerge with an even larger sample or an expanded set of variables, it is noteworthy that, to our knowledge, this is the largest adult MO population to date characterizing physical activity levels and health-related quality of life.

Clinical implications

Considering our results, the management of pain, depressive feelings and lifestyle to lower BMI, seem important components to enhance patients’ PAL. A higher PAL in turn can lead to less disease-related symptoms, psychological factors and lower BMI, creating a reciprocal relationship. Additionally, employment seems to contribute strongest to patients’ PAL and should be addressed in the treatment of working-age patients.

The relationship between the PAL and HRQOL seems rather indirect. We hypothesize that improvement of pain and fatigue, psychological factors and lifestyle leads to a higher PAL, less activity limitations and consequently higher mental and physical HRQOL.

Psychological variables such as depressive symptoms and catastrophizing were present in our sample and showed substantial variability, with depressive symptoms being negatively associated with both PAL and mental HRQOL It cannot be excluded that subgroups exist within the MO population, some of whom experience a larger psychological burden. Consequently, we recommend that psychological variables be routinely assessed and addressed during patient treatment.

Age and educational level were also related to mental and physical HRQOL. Even though these demographic factors are ‘non-modifiable’, they are important to consider during treatment. Focusing on self-efficacy, adequate coping skills and goal-oriented care could enhance patients’ ability to handle disease-related symptoms, help them to adapt to their chronic illness and thus improve their HRQOL.

link